Jeannette Piccard: Blazing a Trail to the Stratosphere

Jeannette Ridlon Piccard (1895-1981) was born to overcome boundaries. A scientist with a strong interest in psychology, philosophy and theology, she dared to dream big, breaking through the metaphorical glass ceiling to become the first female balloon pilot in the US, the first woman to reach the stratosphere, and finally, becoming one of the first 11 female Episcopal priests in the USA.

Dubbed “an adventurous feminine pioneer of the skies,” by the Associated Press, her life’s work ensured that she remains an inspiration to female aviators to this day. And yet, the ground-breaking part she played in the history of aviation and theology as well as her role in the Piccard family is often overshadowed by the work of her husband Jean, her brother-in-law Auguste, her nephew Jacques, her own son Don and – bringing us into the 21st Century – her great-nephew Bertrand Piccard.

“There are hardly any families in the history of exploration with a wider, more ambitious or creative vision” - Neil Armstrong

A strong ambition

Born in 1895, a Victorian upbringing could easily have restricted her ambitious nature, but her father, an orthopedic surgeon, saw the potential in his charismatic and intelligent daughter and supported her studies. She graduated from Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania with a degree in Philosophy and Psychology, going on to study Organic Chemistry at the University of Chicago, receiving her master's degree in 1919.

The organic chemistry in that particular department wasn’t limited to the scientific studies! It was here that she met her husband-to-be, Jean Piccard. Together they were to stake their place in aviation history.

The ‘Century of Progress’

In the early decades of the 1900s, aviation progressed in leaps and bounds, with aircraft flying further and faster than before. There was also a desire to fly ever higher: even to altitudes exceeding 12-15,000m (40-50,000 feet) above which human lungs cannot function unaided.

Jean’s twin brother Auguste had an interest in ballooning and - as a professor of physics - was fascinated by the idea of cosmic radiation. He had been working on a balloon to explore the upper atmosphere, creating a spherical pressurised gondola (inspired by containers for beer) which would allow ascent to such high altitudes without requiring a pressure suit. Auguste’s balloon made a total of 27 flights, reaching an incredible altitude of 23,000m (75,459 feet).

Auguste was approached to design a balloon for the Chicago ‘Century of Progress’ trade show in summer 1933. He declined the offer but recommended his brother Jean for the project.

The duo of Settle and Fordney were first to pilot the “Century of Progress” balloon, achieving an altitude of 18,665 metres (61,237 feet) and setting a FAI world record.

The first female licensed balloon pilot

The Piccards didn’t stop there. In order to continue to carry out scientific tests in the upper atmosphere, and reach ever-loftier altitudes, Jeannette decided that she should gain her balloon pilot’s license so that she could take the helm of the ‘Century of Progress’ whilst Jean concentrated on scientific measurements.

In July 1934, after undertaking the required solo balloon flights in the daytime and at night, Jeannette was awarded her license from the National Aeronautic Association: the very first female licensed balloon pilot in the US.

Not only did Jeannette and Jean have to overcome the scientific challenges to get their balloon aloft, they also had to battle against society’s preconceptions. To gain funding for the project, the Piccards approached various sources who might lend financial support. Not all were forthcoming. Jeannette commented: “The National Geographic Society would have nothing to do with sending a woman—a mother—in a balloon into danger."

Finally, after using the media and commercial contacts to enlist financial support elsewhere, the formidable pilot was ready to take to the air, just three months after she had gained her licence.

The first woman in space

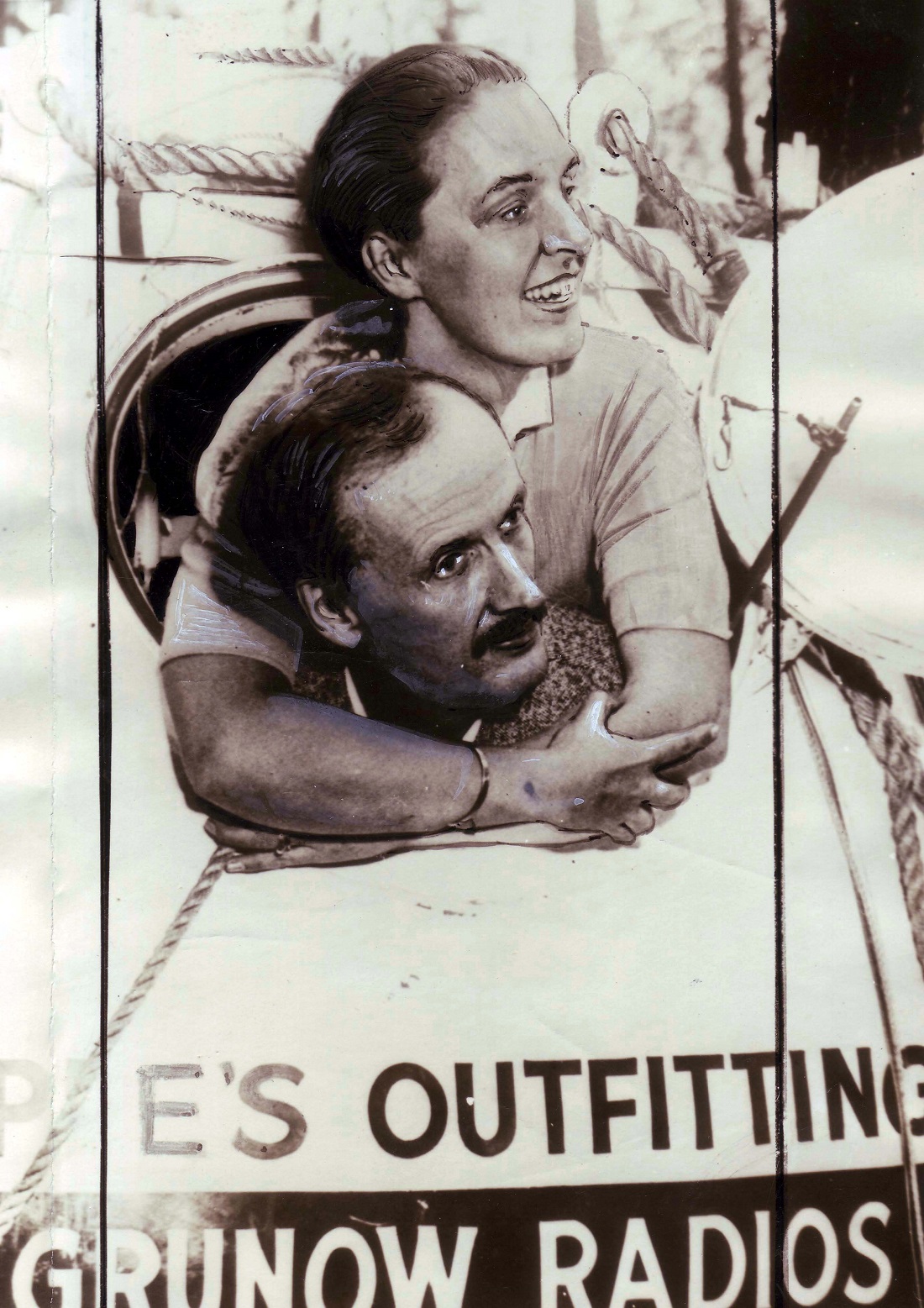

In the early hours of October 23rd 1934, the Century of Progress was released from the airfield in Dearborn, Michigan, kindly loaned for the event by Henry Ford. The balloon floated towards the heavens, as the media and a reported forty-five thousand onlookers cheered it on. Safely ensconced in their pressurised globe were Jeannette, Jean and their pet tortoise, Fleur-de-Lys.

Jeannette controlled the balloon in difficult circumstances, rising through and flying above a layer of clouds that made navigation difficult. During the flight, the Piccards reached 17.5km (10.9 miles), making Jeannette the first woman to pilot an aircraft to the stratosphere.

The balloon made a rather undignified landing in an elm tree in Cadiz, Ohio, but all three occupants were safe. In interviews following the flight, Jeannette felt disappointed that the flight hadn’t been as smooth as she had hoped, but asked if she would repeat the exercise, she responded, "Oh, just give me a chance."

Jeannette Piccard’s balloon flight set the women's altitude record which she held for an incredible 29 years, until Valentina Tereshkova in 1963 became the first woman in space, orbiting the Earth 48 times solo in the Soviet Union's Vostok 6.

Ever aware of her spiritual side, she remarked on the transcendental nature of the experience, saying:

“You feel like part of the air. You almost feel like part of eternity.”

part of the space race

In her later years (after the death of her husband) Jeannette was enlisted by NASA to be a consultant to the director of the Johnson Space Center, a role she undertook from 1964 to 1970. From this perspective, looking back at her career and the progress that had been made since her ground-breaking achievements over 30 years previously, she recognised the part she played in the race to the stratosphere that went on to become the infamous ‘race for space’:

“Working in the (NASA) Space Program, one gets a very rewarding feeling to realise that one has helped give history a little nudge forward toward the wonders of the future.”

a lifetime of breaking boundaries

Upon reaching her ‘70s, Jeannette felt an ever-strong strong pull towards one of her earliest passions – theology. Jeannette had announced to her mother aged only 11 that she wanted to be a priest, an outrageous ambition in the early years of the 20th Century. She was ordained as a deacon in the Episcopal Church in 1971 and three years later, she was – somewhat controversially – ordained as an Episcopal Priest in Philadelphia, together with a group of other female priests who became known as the ‘Philadelphia Eleven’, causing uproar in the Anglican Church. Jeannette’s ordination remained unconfirmed until 1976 – even into her 80s she remained a trail-blazer.

Jeannette passed away from cancer in 1981.

Images courtesy of the Solar Impulse Foundation